How vaccines prevent infections and protect children

Picture yourself in the late 1940s. Parents were afraid to let their children outside, fearing they'd catch the dreaded polio. Most cases were asymptomatic, but more severe cases paralyzed up to 15,000 people every year. After the polio vaccine became widespread, cases dropped. There were less than 10 cases in the 1970s – a shockingly low number for a disease that caused so much panic. Vaccines saved many children from a debilitating disease, and continue to protect children today.

Vaccines protect children

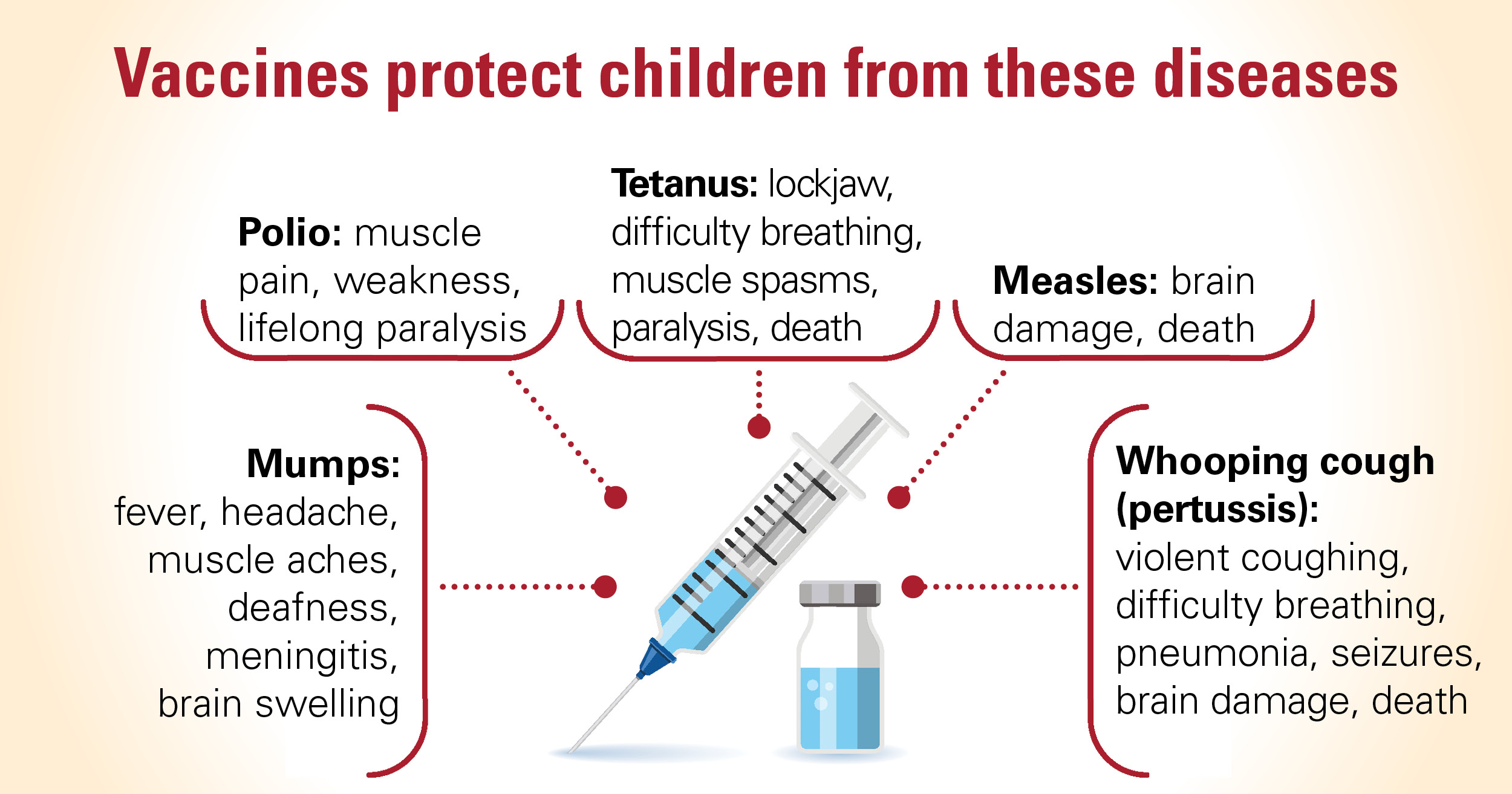

Most children today get lifesaving vaccines against polio, mumps, tetanus, measles, whooping cough and other diseases. Each of these preventable diseases can have serious complications. If we stopped vaccinating children in the United States, these diseases could come back. Vaccines prevent 2 to 3 million deaths every year worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

Measles is one of the world's most contagious diseases. Approximately 90% of unprotected people in close contact with measles will get it. Fortunately, measles was eliminated from the United States in 2000 because of safe, effective vaccines. Then some people refused to vaccinate their children. In 2019, outbreaks in 31 states caused 1,282 cases of measles. The majority of people who got measles were not vaccinated. Vaccinations could have prevented these needless cases.

The risks of vaccines

A vaccine shot hurts. There might be redness or swelling in the area. And they may experience a low-grade fever (99 or 100°F). "An open and honest policy with your children is best. Don't say a shot won't hurt. Prepare them for some temporary pain," says family physician Amber Brown Keebler, MD.

Some parents have decided to not vaccinate their children. This puts their children at risk for several diseases. Children who get these preventable diseases can have lifelong complications and sometimes die.

Your vaccine decisions also affect the people around you. Some vulnerable people can't get a vaccine, often due to a weakened immune system. See recommendations from the CDC on who should not get a vaccine. Your choice to vaccinate yourself and your children helps these vulnerable people stay healthy.

How vaccines work

Why are vaccines necessary? "When we're born, we don't have automatic immunity to many diseases," says Dr. Brown Keebler. "A vaccine gives your immune system a way to fight disease without experiencing the disease itself."

Here's how it works. Either a small amount of a virus or components of a virus are given in a shot. A person's immune system gets alerted to the invader and prepares an attack. The immune system easily fights the (much weakened) invader. Then it gives your immune system a memory of the fight, meaning it can beat the same disease again with even more ease. This body memory is stored in tiny fighters called antibodies.

Keep sick people home to protect others

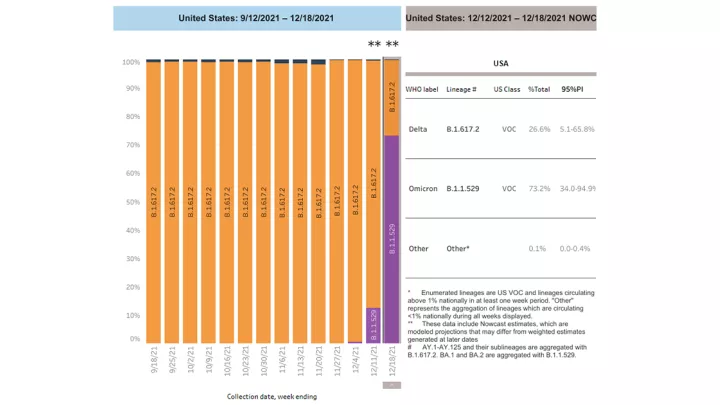

Recent studies estimate one person with COVID-19 infects about six others on average. Since we don't have a COVID-19 vaccine yet, it spreads easily.

"If someone in your household – especially your kids – is sick, keep them home. They may be at a lower risk for severe disease of COVID-19, but many dedicated educators are not low risk," says COVID-19 researcher John Lowe, PhD. To see if your child's symptoms are from COVID-19 or the flu, make an appointment with a pediatrician.

"Until children are able to be vaccinated against COVID-19, we need to require masks in schools to protect students, teachers and everyone else in the community. A lot of teachers, administrators, bus drivers and janitors are high risk. We need to do everything we can to keep them safe," says Dr. Lowe.

In the meantime, it's important to stay up-to-date on other vaccinations to keep your children healthy. "Vaccines and antibiotics together have made the most impact on the public's health by saving countless lives. I have absolute faith in them," says Dr. Brown Keebler.