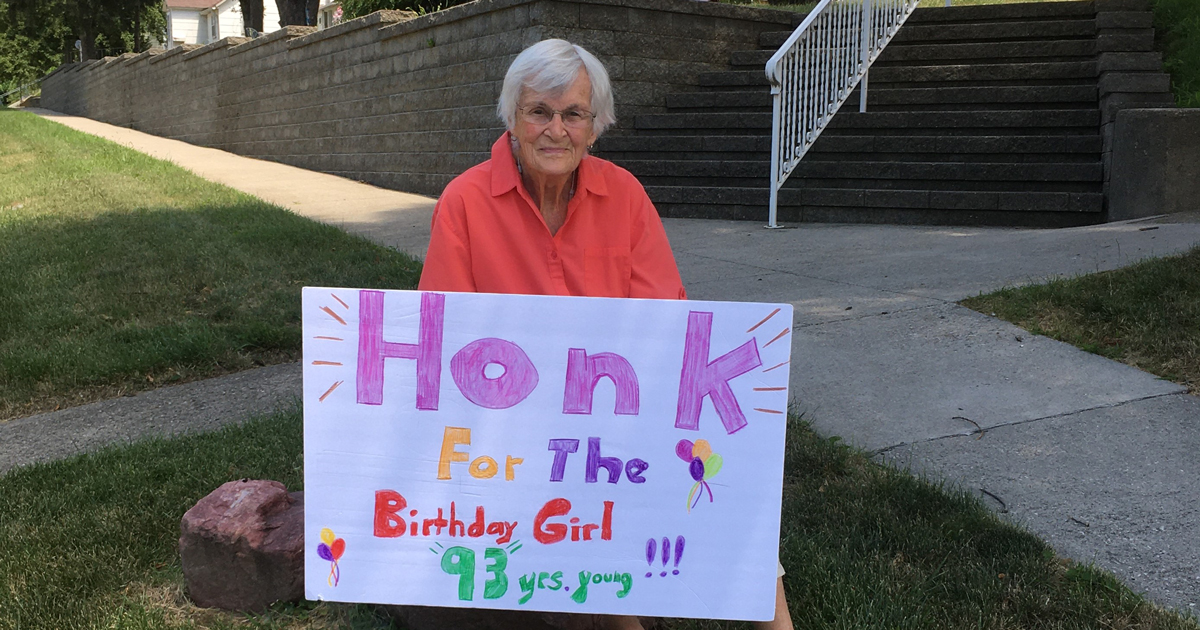

93 year old ready to start living again

Like many of us, Gladys Ahart has been home a lot this past year. At 93 years old, she wasn't willing to risk catching COVID-19. So, she's not sure how long she had been experiencing shortness of breath without realizing it.

"It was winter time, and I had been staying put for most of the year," she says.

After discussing her symptoms with her primary care physician, she was sent for an echocardiogram, which revealed that one of her heart valves was severely blocked, a condition called aortic stenosis. Aortic stenosis can cause the heart to weaken and even fail.

Her physician reached out to William Biddle, MD, cardiologist with Nebraska Medicine, who treats patients at an outreach clinic in Denison, Iowa, for a referral to Nebraska Medical Center.

"Ms. Ahart came to our clinic experiencing shortness of breath and chest heaviness with minimal exertion, like walking around her house," recalls Andrew Goldsweig, MD, a Nebraska Medicine interventional cardiologist who specializes in structural heart disease. "Her echocardiogram revealed blood flow out of her heart was severely limited by a blocked aortic valve. The aortic valve is responsible for regulating blood flow out of the heart, and due to a lifetime of wear and tear, Gladys' aortic valve tissue was thickened, calcified, and rigid, preventing the valve from opening normally."

It was recommended she receive a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), a much less invasive procedure compared to open heart surgery.

"TAVR is the treatment of choice for most patients with severe aortic stenosis," explains Dr. Goldsweig. "TAVR is appropriate for patients at low, intermediate, or high risk for open surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). In the modern era, SAVR is generally reserved for very young patients who need metal, mechanical prosthetic valves or for patients who require another cardiac surgery during the same operation as TAVR."

"They did a good job of explaining what this was," says Ahart.

The night before the procedure, she says she wasn't nervous.

"I'm a pretty laid back person," she says. "I slept well the night before."

In the Cath Lab, a replacement valve was threaded through an artery in her leg to the heart using a catheter. Once in place and expanded, the new valve took over the job of regulating Ahart's blood flow. The procedure took less than two hours and did not require general anesthesia. Glady's TAVR procedure was not only a milestone for her, she was the 600th patient to receive a TAVR at Nebraska Medicine since the procedure was introduced in 2013.

Ahart says the procedure and her recovery went very smoothly.

"It was not a painful procedure," she says. "The recovery was not difficult."

After a short hospital stay, Ahart returned home to find her family extra protective of her health.

"My daughter made a sign for the front door that warned people to keep their distance," she says. "I was horrified at the sign, but the family paid attention."

"I have no doubt this procedure has helped," she continues. "I don't have any shortness of breath. I don't get the chest tightness I used to."

"Prior to the advent of TAVR, people with severe aortic stenosis only had two options: open heart surgery (SAVR) or palliative medications," says Dr. Goldsweig. "Only younger, healthier patients could tolerate open heart surgery, which required up to a week in the hospital and a month of recovery. A 93-year-old like Gladys, who would not have been a candidate for open surgery, would have only received palliative medications, and she would not have lived very long. TAVR has given Gladys the opportunity to enjoy a high quality of life for many more years."

Ahart says she's looking forward to the day she can resume the activities she enjoys, for many reasons. But doing so will allow her to know how far she can push herself.

"Before COVID, I would visit three rest homes each week, I'd go to church every week, play cards with my friends," she says. "It's a long time to be homebound."

She's grateful for a large window in her living room that looks out onto a busy street in her hometown of Denison to help her pass the time. She's been vaccinated, and now hoping for warmer weather and safer conditions for her to get out more. Ahart is the mother of nine children, the grandmother of 16, and the great-grandmother to eight with one on the way.

"I have a lot of living to do," she says.